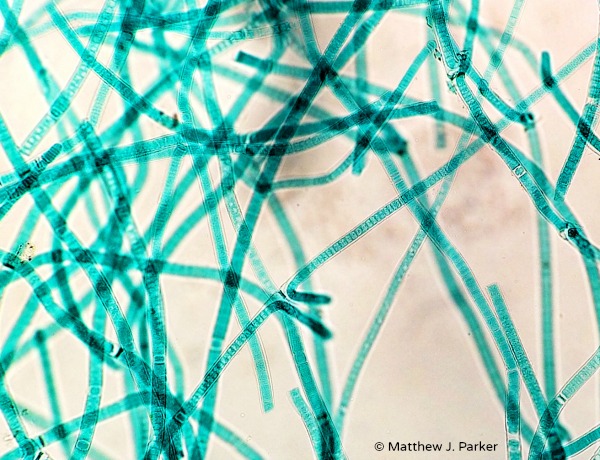

Lagoon cyanobacteria can cause a thick scum on the surface of the water and nasty odors. During the summer, the combination of sunlight, warm water temperatures, high nutrient loads, and predation by higher life forms like Daphnia and rotifers can lead to rampant algal growth, or blooms. Cyanobacteria are classified by the EPA as harmful algal blooms, or HABs, because they cause eutrophication or dead zones and can even release toxins that are harmful or deadly to people and animals.

What is lagoon cyanobacteria?

Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are neither bacteria nor algae. They are algae-ish, growing like regular green algae and often forming scummy mats on the water’s surface. Because they outcompete green algae, excessive blue-green algae cause low dissolved oxygen (DO) conditions at the bottom of a lagoon, with mats blocking sunlight and the surface interface with the air.

Cyanobacteria are classified by the EPA as harmful algal blooms, or HABs, because they can cause environmental damage and health problems. According to the EPA, microcystis is the most common bloom-forming type of cyanobacteria, and it’s almost always toxic. Even after the blooms die, high concentrations of toxins may continue to leach into the water for months.

Exposure to microcystins, the toxic byproduct of blue-green algae, can cause liver damage and skin, eye, and throat irritation, and can be deadly to pets and wildlife. A bloom of blue-green algae across the Mississippi coast caused the closure of all 21 beaches. Chicago’s Humboldt Park recreational lagoon, once famous as the home of a renegade alligator, was forced to warn visitors away from the water due to toxic algae.

Microcystis creates a thick, paint-like coating on the surface of the water and around the edges, and its odor has been compared to a combination of “rotten meat and cat litter.”

The Effluent Connection

The EPA cites nutrient pollution—originating from agricultural and stormwater runoff, the burning of fossil fuels, and wastewater—as one of the main causes of HABs. Climate change is a contributing factor, causing warmer temperatures and heavier rains that wash fertilizers off fields and into waterways.

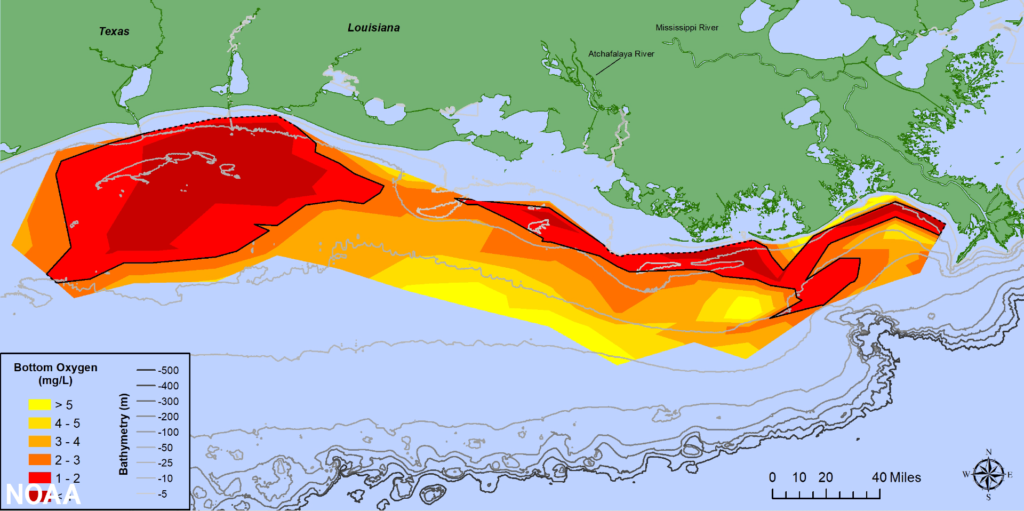

Nutrient runoff contributes to hypoxia and toxic algae. As illustrated above, NOAA reported a Gulf of Mexico dead zone of over 6,300 square miles—higher than the five year average of 5,380 square miles—in 2021.

Because of high nutrient levels causing eutrophication, dead zones, and HABs, the EPA has been cracking down on effluent ammonia and phosphorus in wastewater. While not every state or every facility has ammonia and phosphorus limits, depending on the quality of the local waterways and whether they have Total Maximum Daily Loads, or TMDLs (more about TMDLs here), it’s likely that over time, virtually every discharging wastewater facility will have them. And that includes wastewater lagoons, which were never designed to remove ammonia and phosphorus.

High effluent nutrient levels, especially phosphorus, lead to the development of HABs in waterways. HABs can also be a problem in the lagoon.

Toxic Blue-Green Algae in the Wastewater Lagoon

In summer, an insufficiently mixed and aerated lagoon is susceptible to blooms of toxic blue-green algae. High BOD and nutrient loading and stagnancy are the main culprits, so a bloom of blue-green algae indicates poor conditions: organic overloading, low dissolved oxygen, and a lack of sufficient aeration.

Lagoon cyanobacteria blooms interfere with treatment by increasing biological oxygen demand (BOD) and suspended solids (TSS), and, as they die off, contribute to the accumulation of sludge. A wastewater lagoon with blue-green algae is at risk of violating for BOD, TSS, and effluent phosphorus, as well as for generating complaints about the scummy appearance and foul odors.

The Wisconsin DNR’s Wastewater Operator Certification Study Guide for lagoons suggests several corrective actions for algae blooms:

- Discharge effluent from below the surface, where algae is less concentrated

- Reduce organic loading, especially from industrial sources

- Add barley straw around the perimeter in the spring; as it decomposes, it inhibits the growth of algae

- Add a dye or cover to the final cell to block sunlight

- Use the cell with the best water quality for discharge; let the others rest until the algae die off

- Add aeration

The use of chemicals—metal salts to precipitate phosphorus, or algicides like copper sulfate or potassium permanganate—is an option, but it’s not ideal. Adding chemicals can disrupt the natural treatment process, killing not just algae but all the friendly bugs, too. Also, chemical usage in a lagoon may be highly regulated. Check with your local regulatory agency for guidance.

Blue-green algae, whether in your lagoon or in your local waterway, will get regulators breathing down your neck. Lagoon cyanobacteria will likely put you out of permit for BOD and TSS; in your local waterway, it may trigger an ammonia or phosphorus limit on your facility.